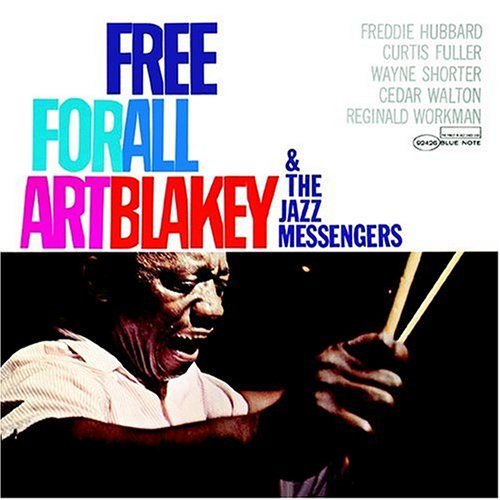

Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers Free for All

Of the several dozen studio albums recorded by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, none possess the sheer power and ferocious intensity of "Gratis for All". Recorded on February 10, 1964, it marked the Messengers first recording for Blue Notation in about two years, and its palpable free energy made this studio recording sound similar a live date. Nat Hentoff's original liner notes state that on the evening of the recording, "Blakey was in a more galvanized land than…on any of his previous Blue Annotation dates" and that Blakey'southward energy inspired the residue of the band. Yet Hentoff never says what events—individual or public—triggered those emotions.

Of the several dozen studio albums recorded by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, none possess the sheer power and ferocious intensity of "Gratis for All". Recorded on February 10, 1964, it marked the Messengers first recording for Blue Notation in about two years, and its palpable free energy made this studio recording sound similar a live date. Nat Hentoff's original liner notes state that on the evening of the recording, "Blakey was in a more galvanized land than…on any of his previous Blue Annotation dates" and that Blakey'southward energy inspired the residue of the band. Yet Hentoff never says what events—individual or public—triggered those emotions.

February 1964 was a turbulent time. In the first week alone, at that place was a cold-shoulder of New York Urban center'south public schools by black and Puerto Rican students because of declared de facto segregation; the trial of the accused murderer of civil rights leader Medgar Evers ended in a mistrial when the all-white Mississippi jury was unable to accomplish a verdict; and on the dark earlier the "Free For All" recording session, the Beatles made their beginning live appearance on "The Ed Sullivan Bear witness". The well-known image of screaming teenage girls in Sullivan'due south audition made it clear that the Beatles were about to modify the landscape of the music scene.

However, much of the Messengers' ongoing inspiration came from John Coltrane, whose marathon performances were generating previously unheard levels of intensity, and whose modal improvisations offered no sense of harmonic resolution. Blakey's sidemen were writing tunes with delayed harmonic resolutions, and two of those compositions were the first pieces recorded for "Gratuitous for All". Except for Wayne Shorter, every member of the Messengers (Freddie Hubbard, Curtis Fuller, Cedar Walton, Reggie Workman and Blakey) had recorded with Coltrane, and Shorter was considered 1 of Coltrane's greatest disciples (a reputation that peaked that summertime with Shorter's Blue Note anthology "Juju", featuring Coltrane sidemen McCoy Tyner, Workman and Elvin Jones).

Regardless of which events prompted the explosive music on "Gratis for All", Blakey and the Messengers seemed determined to display the emotional and artistic validity of their music, as well as a strong delivery to the civil rights movement. The session opened with "The Core", which Hubbard dedicated to the Congress for Racial Equality, a group in the news for their efforts in registering blackness voters in the Deep S. The peppery horn solos are backed by Blakey's kinetic cantankerous-rhythms and Walton's Tyner-influenced comping. The horn backgrounds inserted at central moments simply increase the intensity. Engineer Rudy Van Gelder must take been surprised at the sheer book coming from the studio flooring, for the recording has an unusually high amount of distortion on the horn and drum mikes. "Hammerhead" is as aggressive, and Blakey'south shell seems designed to reinterpret "The Blues March" for a new age. With the recording levels readjusted, the rest is clearer betwixt the rhythm section and the horns, and nosotros can hear Blakey vocally encouraging the soloists. Blakey's exhortations inspire the soloists, raise the overall intensity, and innovate a unique character to the album.

With one-half of the new album finished, the drummer's cousin, singer Wellington Blakey joined the group for versions of "My Funny Valentine" and "Soul Lady". By 1964, Wellington's checkered career in R&B groups had yielded very few recordings. His style was reminiscent of Roy Milton, and King of beasts and Wolff may have considered issuing a 45 rpm single of Wellington'south tracks. Instead, the tracks were rejected and never issued. Wellington was back with the Messengers ten days later, when they recorded their Riverside LP, "Kyoto", and this fourth dimension "Wellington's Dejection" made it onto the anthology. This bland, undistinguished title may accept been Wellington's concluding recording. After Wellington'southward spot, the Messengers recorded "Eva", a carol they had recorded at Birdland for the Riverside album, "Ugetsu", but which had been left off the LP. Blue Annotation rejected the studio version, probably because the piece that followed it was lyrical enough to rest the album. That slice was Clare Fischer'due south "Pensativa", certainly the virtually-covered slice of all the tracks on "Free for All". Hubbard heard the piece during a gig on Long Island and was then captivated by the melody that he brought it into the Messengers' book. The piece is ostensibly a bossa nova, but Blakey avoids the traditional samba beat and plays a deliciously loose and swinging Latin groove. Hubbard and Fuller share Fischer's glorious melody, and Hubbard'south solo is ane of his all-fourth dimension best, balancing abstract length phrases and unadulterated lyricism. Shorter is more melodic here than anywhere else on the anthology, and Walton sparkles through his beautifully-crafted solo. Although Hubbard recorded an extended version of "Pensativa" on the 1965 Blue Note anthology, "The Dark of the Cookers", it is the rendition on "Gratuitous for All" that remains the undisputed archetype.

The title runway (which opens the album) was actually the terminal melody recorded at the session. The Messengers were ready to wail once again, and the intensity on this rails actually exceeded their piece of work from earlier in the evening. Shorter's explosive solo is fueled by Blakey's astonishing polyrhythms, and an unsuspecting listener to this excerpt might mistake the players for Coltrane and Elvin Jones. Fuller is up next with a forceful statement that builds tension with its precise rhythms and accent on a key pitch. Hubbard'due south solo is rhythmically complex, and he is in perfect synch with the cantankerous-rhythms played by the rhythm section. Blakey roars into his only solo spot on the anthology, creating a sound that is remarkably dense, even for him.

"Free for All" represents the artistic zenith of the Messengers with Hubbard, Fuller and Shorter. The aforementioned "Kyoto" would be their last album together as a sextet. By April, when the Messengers recorded their next Blue Annotation album "Indestructible", Lee Morgan was dorsum in the trumpet chair. Most of the musicians did occasional recordings equally leaders and free-lancers, only Shorter's tenure with Miles Davis would begin a new management in his musical development. Blakey continued to notice new young players until he passed in 1990, but while many of his later recordings were very heady, few of them captured the overwhelming energy as well equally those captured in the grooves of "Free for All".

Source: https://jazzhistoryonline.com/art-blakey-free-for-all/

0 Response to "Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers Free for All"

Post a Comment