How Would Fdr Feel About the Hawley-smoot Tariff? How Do You Know This?

| |

| Long title | An Act To provide revenue, to regulate commerce with foreign countries, to encourage the industries of the United States, to protect American labor, and for other purposes. |

|---|---|

| Nicknames | Smoot–Hawley Tariff, Hawley–Smoot Tariff |

| Enacted by | the 71st United states of america Congress |

| Constructive | March 13, 1930 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | Pub.50. 71–361 |

| Statutes at Large | ch. 497, 46 Stat. 590 |

| Codification | |

| UsaC. sections created | 589 |

| Legislative history | |

| |

The Tariff Act of 1930 (codified at nineteen U.South.C. ch. 4), commonly known as the Smoot–Hawley Tariff or Hawley–Smoot Tariff,[1] was a law that implemented protectionist trade policies in the United States. Sponsored by Senator Reed Smoot and Representative Willis C. Hawley, it was signed by President Herbert Hoover on June 17, 1930. The deed raised US tariffs on over 20,000 imported goods.[2]

The tariffs nether the human activity, excluding duty-gratis imports (see Tariff levels below), were the second highest in United States history, exceeded by only the Tariff of 1828.[3] The Act prompted retaliatory tariffs past affected states against the U.s..[4] The Act and tariffs imposed by America'due south trading partners in retaliation were major factors of the reduction of American exports and imports by 67% during the Depression.[5] Economists and economic historians have a consensus view that the passage of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff worsened the effects of the Nifty Depression.[6]

Sponsors and legislative history [edit]

Willis C. Hawley (left) and Reed Smoot in Apr 1929, shortly before the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act passed the House of Representatives.

In 1922, Congress passed the Fordney–McCumber Tariff Act, which increased tariffs on imports.[ citation needed ]

The League of Nations' World Economical Conference met at Geneva in 1927, concluding in its terminal report: "the time has come to put an stop to tariffs, and to movement in the reverse direction." Vast debts and reparations could be repaid only through gold, services, or goods, only the only items available on that scale were goods. However, many of the delegates' governments did the opposite; in 1928, French republic was the first by passing a new tariff police and quota system.[7]

By the late 1920s, the US economy had fabricated infrequent gains in productivity because of electrification, which was a critical cistron in mass product. Besides, horses and mules had been replaced by motorcars, trucks, and tractors. One sixth to one quarter of farmland, which had been devoted to feeding horses and mules, was freed up, contributing to a surplus in farm produce. Although nominal and real wages had increased, they did not proceed up with the productivity gains. As a effect, the power to produce exceeded market place demand, a condition that was variously termed overproduction and underconsumption.[ citation needed ]

Senator Smoot contended that raising the tariff on imports would convalesce the overproduction trouble, only the United States had actually been running a merchandise account surplus, and although manufactured goods imports were rising, manufactured exports were rising even faster. Food exports had been falling and were in trade account deficit, just the value of food imports were a picayune over half of the value of manufactured imports.[viii]

As the global economy entered the commencement stages of the Great Depression in late 1929, the main goal of the US was to protect its jobs and farmers from foreign competition. Smoot championed another tariff increase inside the Us in 1929, which became the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Pecker. In his memoirs, Smoot made it abundantly articulate:

The globe is paying for its ruthless destruction of life and property in the Globe War and for its failure to adjust purchasing power to productive chapters during the industrial revolution of the decade following the war.[ix]

Smoot was a Republican from Utah and chairman of the Senate Finance Committee. Willis C. Hawley, a Republican from Oregon, was chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee.[ citation needed ]

During the 1928 presidential election, i of Herbert Hoover's promises was to help beleaguered farmers past increasing tariffs on agricultural products. Hoover won, and Republicans maintained comfy majorities in the House and the Senate during 1928. Hoover then asked Congress for an increase of tariff rates for agricultural goods and a decrease of rates for industrial goods.[ citation needed ]

Senate vote by state

Ii Yeas

2 Nays

1 Yea and One Nay

One Yea and One Avoidance

One Nay and I Abstention

Ii Abstentions

The House passed a version of the act in May 1929, increasing tariffs on agronomical and industrial goods akin. The Firm beak passed on a vote of 264 to 147, with 244 Republicans and twenty Democrats voting in favor of the nib.[x] The Senate debated its bill until March 1930, with many members trading votes based on their states' industries. The Senate bill passed on a vote of 44 to 42, with 39 Republicans and 5 Democrats voting in favor of the bill.[ten] The conference committee then unified the two versions, largely by raising tariffs to the college levels passed past the House.[xi] The Firm passed the conference neb on a vote of 222 to 153, with the back up of 208 Republicans and xiv Democrats.[10]

Opponents [edit]

In May 1930, a petition was signed by one,028 economists in the United States asking President Hoover to veto the legislation, organized by Paul Douglas, Irving Fisher, James T.F.G. Woods, Frank Graham, Ernest Patterson, Henry Seager, Frank Taussig, and Clair Wilcox.[12] [thirteen] Automobile executive Henry Ford also spent an evening at the White House trying to convince Hoover to veto the bill, calling it "an economic stupidity",[14] while J. P. Morgan'southward Chief Executive Thomas West. Lamont said he "almost went down on [his] knees to beg Herbert Hoover to veto the asinine Hawley–Smoot tariff".[15]

While Hoover joined the economists in opposing the bill, calling it "vicious, extortionate, and obnoxious" because he felt information technology would undermine the delivery he had pledged to international cooperation, he eventually signed the bill later he yielded to influence from his own party, his Chiffonier (who had threatened to resign), and concern leaders.[xvi]

Hoover'due south fears were well founded, as Canada and other countries raised their own tariffs in retaliation after the bill had go police force.[17]

Franklin D. Roosevelt spoke against the act during his campaign for President in 1932.[11]

Retaliation [edit]

Most of the refuse in trade was due to a plunge in GDP in the United states and worldwide. Nonetheless beyond that was boosted reject. Some countries protested and others likewise retaliated with merchandise restrictions and tariffs. American exports to the protesters fell 18% and exports to those who retaliated brutal 31%.[eighteen]

Threats of retaliation past other countries began long before the bill was enacted into law in June 1930. As the House of Representatives passed it in May 1929, boycotts broke out, and foreign governments moved to increment rates confronting American products, although rates could be increased or decreased past the Senate or past the conference commission. By September 1929, Hoover's administration had received protest notes from 23 trading partners, just the threats of retaliatory actions were ignored.[11]

In May 1930, Canada, the country'due south about loyal trading partner, retaliated by imposing new tariffs on 16 products that accounted altogether for around 30% of U.s. exports to Canada.[19] Canada later besides forged closer economic links with the British Empire via the British Empire Economic Conference of 1932, while France and Uk protested and adult new trade partners, and Federal republic of germany developed a organization of trade via clearing.

The depression worsened for workers and farmers despite Smoot and Hawley's promises of prosperity from high tariffs; consequently, Hawley lost re-nomination, while Smoot was one of 12 Republican Senators who lost their seats in the 1932 elections, with the swing being the largest in Senate history (being equalled in 1958 and 1980).[20]

Tariff levels [edit]

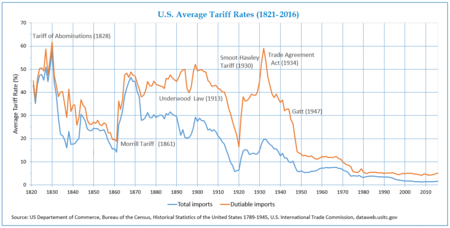

Average Tariff Rates in United states (1821–2016)

In the ii-volume serial published by the US Agency of the Census, "The Historical Statistics of the U.s.a., Colonial Times to 1970, Bicentennial Edition", tariff rates have been represented in 2 forms. The dutiable tariff rate elevation of 1932 was 59.1%, 2nd but to the 61.7% rate of 1830.[21]

Nonetheless, 63% of all imports in 1933 were not taxed, which the dutiable tariff rate does not reverberate. The free and dutiable rate in 1929 was 13.5%, and peaked under Smoot–Hawley in 1933 at 19.viii%, ane-third below the average 29.7% "free and dutiable rate" in the United States from 1821 to 1900.[22]

The boilerplate tariff rate on dutiable imports[23] [24] increased from xl.one% in 1929 to 59.1% in 1932 (+19%). Nonetheless, it had already been consistently at high levels betwixt 1865 and 1913 (from 38% to 52%), and it had also risen sharply in 1861 (from 18.61% to 36.two%; +17.59%), between 1863 and 1866 (from 32.62% to 48.33%; +xv.71%), and betwixt 1920 and 1922 (from 16.4% to 38.1%; +21.7%) without producing global depressions.[ citation needed ]

Afterward enactment [edit]

At start, the tariff seemed to be a success. According to historian Robert Sobel, "Factory payrolls, structure contracts, and industrial production all increased sharply." However, larger economic issues loomed in the guise of weak banks. When the Creditanstalt of Austria failed in 1931, the global deficiencies of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff became apparent.[sixteen]

US imports decreased 66% from $four.four billion (1929) to $1.5 billion (1933), and exports decreased 61% from $v.four billion to $2.i billion. GNP savage from $103.1 billion in 1929 to $75.8 billion in 1931 and bottomed out at $55.6 billion in 1933.[25] Imports from Europe decreased from a 1929 loftier of $one.3 billion to just $390 1000000 during 1932, and US exports to Europe decreased from $2.iii billion in 1929 to $784 1000000 in 1932. Overall, globe trade decreased by some 66% betwixt 1929 and 1934.[26]

Using panel data estimates of consign and import equations for 17 countries, Jakob B. Madsen (2002) estimated the effects of increasing tariff and not-tariff trade barriers on worldwide merchandise from 1929 to 1932. He concluded that real international trade contracted somewhere around 33% overall. His estimates of the impact of various factors included almost 14% because of failing GNP in each land, viii% because of increases in tariff rates, v% considering of deflation-induced tariff increases, and six% because of the imposition of non-tariff barriers.[ citation needed ]

The new tariff imposed an effective tax rate of 60% on more than three,200 products and materials imported into the United States, quadrupling previous tariff rates on private items but raising the boilerplate tariff rate to 19.ii%, which was in line with average rates of that twenty-four hour period.[ commendation needed ]

Unemployment was viii% in 1930 when the Smoot–Hawley Human action was passed, just the new law failed to lower it. The rate jumped to 16% in 1931 and 25% in 1932–1933.[27] There is some contention about whether this tin can necessarily be attributed to the tariff, however.[28] [29]

It was only during Earth War Ii, when "the American economy expanded at an unprecedented charge per unit",[30] that unemployment fell beneath 1930s levels.[31]

Imports during 1929 were only 4.two% of the The states GNP, and exports were simply v.0%. Monetarists, such as Milton Friedman, who emphasize the central role of the money supply in causing the depression, consider the Smoot–Hawley Deed to be only a minor crusade for the United states Great Depression.[32]

Terminate of tariffs [edit]

The 1932 Democratic campaign platform pledged to lower tariffs. After winning the election, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the now-Democratic Congress passed Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934. This act allowed the President to negotiate tariff reductions on a bilateral basis and treated such a tariff understanding as regular legislation, requiring a majority, rather than as a treaty requiring a ii-thirds vote. This was one of the core components of the trade negotiating framework that adult afterwards Earth State of war Two. The tit-for-tat responses of other countries were understood to have contributed to a abrupt reduction of merchandise in the 1930s.[ citation needed ]

After World War II, that understanding supported a push towards multilateral trading agreements that would preclude similar situations in the future. While the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944 focused on strange exchange and did not directly address tariffs, those involved wanted a similar framework for international merchandise. President Harry S. Truman launched this process in November 1945 with negotiations for the creation of a proposed International Merchandise Organization (ITO).[33]

As it happened, split up negotiations on the Full general Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) moved more quickly, with an agreement signed in October 1947; in the stop, the United States never signed the ITO agreement. Adding a multilateral "most-favored-nation" component to that of reciprocity, the GATT served equally a framework for the gradual reduction of tariffs over the subsequent half century.[34]

Postwar changes to the Smoot–Hawley tariffs reflected a general tendency of the United States to reduce its tariff levels unilaterally while its trading partners retained their high levels. The American Tariff League Report of 1951 compared the costless and dutiable tariff rates of 43 countries. Information technology found that just vii nations had a lower tariff level than the United States (5.1%), and eleven nations had free and dutiable tariff rates higher than the Smoot–Hawley pinnacle of nineteen.8% including the United kingdom (25.6%). The 43-country average was 14.4%, which was 0.9% higher than the U.S. level of 1929, demonstrating that few nations were reciprocating in reducing their levels as the United States reduced its ain.[35]

In modern political dialogue [edit]

In the discussion leading up to the passage of the North American Free Merchandise Agreement (NAFTA) then-Vice President Al Gore mentioned the Smoot–Hawley Tariff as a response to NAFTA objections voiced by Ross Perot during a argue in 1993 they had on The Larry King Prove. He gave Perot a framed picture of Smoot and Hawley shaking hands afterward its passage.[11]

In April 2009, and so-Representative Michele Bachmann fabricated news when, during a speech, she referred to the Smoot-Hawley Tariff as "the Hoot-Smalley Act", misattributed its signing to Franklin Roosevelt, and blamed information technology for the Neat Low.[36] [37] [38]

The act has been compared to the 2010 Strange Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA), with Andrew Quinlan from the Middle for Freedom and Prosperity calling FATCA "the worst economic thought to come out of Congress since Smoot–Hawley".[39]

Forced labor [edit]

Prior to 2016, the Tariff Act provided that "[a]ll goods, wares, articles, and merchandise mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part in any strange country by convict labor or/and forced labor or/and indentured labor under penal sanctions shall not be entitled to entry at any of the ports of the United states" with a specific exception known every bit the "consumptive demand exception", which allowed forced labor-based imports of goods where United States domestic production was not sufficient to meet consumer demand.[40] The exception was removed under Wisconsin Representative Ron Kind's amendment bill, which was incorporated into the Merchandise Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015, signed by President Barack Obama on 24 February 2016.[41]

Encounter also [edit]

- Country-of-origin labeling

- International trade

- Found Patent Act of 1930 (originally enacted as Championship Three of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act)

- Trade war

References [edit]

- ^ ch. 497, 46 Stat. 590, June 17, 1930, run into 19 U.Due south.C. § 1654

- ^ Taussig (1931)

- ^ WWS 543: Course notes, 2/17/10, Paul Krugman, February 16, 2010, Presentation, slide iv

- ^ "The Smoot-Hawley Merchandise War". Economic Journal. 2022.

- ^ Alfred East. Eckes, Jr., Opening America's Market: U.S. Foreign Trade Policy Since 1776 (University of North Carolina Press, 1995, pp. 100–03)

- ^ Whaples, Robert (March 1995). "Where Is There Consensus Among American Economic Historians? The Results of a Survey on Forty Propositions" (PDF). The Journal of Economic History. Cambridge Academy Press. 55 (one): 144. CiteSeerXx.1.1.482.4975. doi:ten.1017/S0022050700040602. JSTOR 2123771.

- ^ The War: the root and remedy, George Peel, 1941

- ^ Beaudreau, Bernard C. (1996). Mass Production, the Stock Market place Crash and the Nifty Depression. New York, Lincoln, Shanghi: Authors Choice Press.

- ^ Merill, Milton (1990), Reed Smoot: Apostle in Politics, Logan, UT: Utah Land Press, p. 340, ISBN0-87421-127-one .

- ^ a b c Irwin, Douglas A.; Randall Southward. Kroszner (Dec 1996). "Log-Rolling and Economical Interests in the Passage of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff" (PDF). Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy. 45: 6. doi:10.1016/s0167-2231(96)00023-one. S2CID 154857884. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c d "The Boxing of Smoot–Hawley", The Economist, December 18, 2008 .

- ^ "i,028 Economists Ask Hoover To Veto Pending Tariff Bill: Professors in 179 Colleges and Other Leaders Assail Rise in Rates as Harmful to State and Sure to Bring Reprisals" (PDF), The New York Times, May v, 1930, archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2008 .

- ^ "Economists Against Smoot–Hawley", Econ Journal Scout, September 2007 .

- ^ "Shades of Smoot–Hawley", Time, October 7, 1985, archived from the original on October 29, 2010 .

- ^ Chernow, Ron (1990), The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance, New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, p. 323, ISBN0-87113-338-5 .

- ^ a b Sobel, Robert (1972), The Age of Giant Corporations: A Microeconomic History of American Business, 1914–1970, Westport: Greenwood Press, pp. 87–88, ISBN0-8371-6404-iv .

- ^ Steward, James B. (March 8, 2018). "What History Has to Say most the 'Winners' in Merchandise Wars". The New York Times. No. International edition. New York, N.Y. Retrieved November vii, 2021.

- ^ Kris James Mitchener, Kirsten Wandschneider, and Kevin Hjortshøj O'Rourke. "The Smoot-Hawley Trade War" (No. w28616. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021) online.

- ^ Dark-brown, Wilson B. & Hogendorn, Jan S. (2000), International Economics: In the Age of Globalization, Toronto: University of Toronto Printing, p. 246, ISBN1-55111-261-2 .

- ^ Rhodri Jeffreys-Jones (1997). Changing Differences: Women and the Shaping of American Foreign Policy, 1917–1994. Rutgers University Printing. p. 48.

- ^ https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/03/22/u-s-tariffs-are-amidst-the-lowest-in-the-world-and-in-the-nations-history/

- ^ The Historical Statistics of the Us, Colonial Times to 1970, Bicentennial Edition. Vol. Part two. U.Southward. Census Bureau. p. 888. Table: Serial U207-212 (Role 2 ZIP file: file named CT1970p2-08.pdf).

- ^ https://www.usitc.gov/documents/dataweb/ave_table_1891_2016.pdf[ bare URL PDF ]

- ^ Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1957. 1960.

- ^ Agency of the Census, Historical Statistics series F-1

- ^ Jones, Joseph Marion (June 21, 2003), "Smoot–Hawley Tariff", U.S. Department of Land, ISBN0-8240-5367-2, archived from the original on March 12, 2009 .

- ^ .

- ^ Eckes, p. 113

- ^ Douglas A. Irwin, "The Smoot–Hawley Tariff: A Quantitative Cess", The Review of Economic science and Statistics, Vol. fourscore, No.ii, The MIT Press, May 1998, pp. 332–33.

- ^ Tassava, Christopher. "The American Economy during World War Two". EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. February ten, 2008.

- ^ Bureau of Labor Statistics, "Graph of U.S. Unemployment Charge per unit, 1930–1945", HERB: Resources for Teachers, retrieved Apr 24, 2015.

- ^ Milton Friedman and Anna Jacobson Schwartz, A monetary history of the United States, 1867–1960 (1963) p. 342

- ^ "Argument by the President on the Forthcoming International Conference on Tariffs and Trade". Harry South. Truman Library & Museum.

- ^ "Understand the WTO: The GATT years: from Havana to Marrakesh", World Trade Organization .

- ^ Lloyd, Lewis E. Tariffs: The Instance for Protection. The Devin-Adair Co., 1955, Appendix, Table Half-dozen, pp. 188–89

- ^ Steve Benen (Apr 30, 2009). "'Hoot-Smalley'". Washington Monthly . Retrieved Dec ten, 2021.

- ^ Eric Kleefeld (April 29, 2009). "Historian Michele Bachmann Blames FDR's 'Hoot-Smalley' Tariffs For Great Depression". Talking Points Memo . Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- ^ Matthew Yglesias (April 29, 2009). "Michelle Bachmann Embraces Ignorance, Contrary Causation". ThinkProgress. Archived from the original on May 2, 2009.

- ^ "Senator Rand Paul Introduces Bill to Repeal FATCA!".

- ^ Section 307 of the Tariff Act of 1930, quoted in Altschuller, S., U.S. Congress Finally Eliminates the Consumptive Demand Exception, Global Business and Human Rights, published by Foley Hoag LLP, 16 Feb 2016, accessed 22 November 2020

- ^ GovTrack.us, H.R. 1903 (114th): To meliorate the Tariff Act of 1930 to eliminate the consumptive demand exception to prohibition on importation of goods made with captive labor, forced labor, or indentured labor, and for other purposes, accessed 22 Nov 2020

Heavily featured in the book "Dave Barry Slept Hither: a sort of history of the United States" by Dave Barry.

Sources [edit]

- Archibald, Robert B.; Feldman, David H. (1998), "Investment During the Great Depression: Doubtfulness and the Role of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff", Southern Economical Journal, 64 (four): 857–79, doi:10.2307/1061208, JSTOR 1061208

- Crucini, Mario J. (1994), "Sources of variation in real tariff rates: The United States 1900 to 1940", American Economic Review, 84 (iii): 346–53, JSTOR 2118081

- Crucini, Mario J.; Kahn, James (1996), "Tariffs and Aggregate Economic Activity: Lessons from the Dandy Depression", Periodical of Monetary Economics, 38 (3): 427–67, doi:10.1016/S0304-3932(96)01298-6

- Eckes, Alfred (1995), Opening America's Market place: U.Southward. Foreign Merchandise Policy since 1776, Chapel Hill: Academy of North Carolina Printing, ISBN0-585-02905-ix

- Eichengreen, Barry (1989), "The Political Economic system of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff", Research in Economic History, 12: 1–43

- Irwin, Douglas (1998), "The Smoot–Hawley Tariff: A Quantitative Assessment" (PDF), Review of Economic science and Statistics, fourscore (2): 326–34, doi:10.1162/003465398557410, S2CID 57562207

- Irwin, Douglas (2011), Peddling Protectionism: Smoot–Hawley and the Groovy Depression, Princeton Academy Press, ISBN978-0-691-15032-1

- Kaplan, Edward S. (1996), American Trade Policy: 1923–1995, London: Greenwood Press, ISBN0-313-29480-1

- Kottman, Richard Northward. (1975), "Herbert Hoover and the Smoot–Hawley Tariff: Canada, A Example Study", Journal of American History, 62 (3): 609–35, doi:10.2307/2936217, JSTOR 2936217

- Koyama, Kumiko (2009), "The Passage of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act: Why Did the President Sign the Bill?", Journal of Policy History, 21 (2): 163–86, doi:10.1017/S0898030609090071, S2CID 154415038

- McDonald, Judith; O'Brien, Anthony Patrick; Callahan, Colleen (1997), "Merchandise Wars: Canada'due south Reaction to the Smoot–Hawley Tariff", Journal of Economic History, 57 (four): 802–26, doi:10.1017/S0022050700019549, JSTOR 2951161

- Madsen, Jakob B. (2001), "Trade Barriers and the Collapse of World Trade during the Smashing Low", Southern Economical Periodical, 67 (4): 848–68, doi:ten.2307/1061574, JSTOR 1061574

- Merill, Milton (1990), Reed Smoot: Apostle in Politics, Logan, UT: Utah Land Press, ISBN0-87421-127-one

- Mitchener, Kris James, Kirsten Wandschneider, and Kevin Hjortshøj O'Rourke. "The Smoot-Hawley Trade War" (No. w28616. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021) online.

- O'Brien, Anthony, "Smoot–Hawley Tariff", EH Encyclopedia, archived from the original on Oct 2, 2009

- Pastor, Robert (1980), Congress and the Politics of U.S. Foreign Economic Policy, 1929–1976, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN0-520-03904-1

- Schattschneider, E. Due east. (1935), Politics, Pressures and the Tariff, New York: Prentice-Hall – Archetype study of passage of Hawley–Smoot Tariff

- Taussig, F. W. (1931), The Tariff History of the United states of america (PDF) (8th ed.), New York: G. P. Putnam'southward Sons

- Temin, Peter (1989), Lessons from the Peachy Low , Cambridge, MA: MIT Printing, ISBN0-262-20073-2

- Turney, Elaine C. Prange; Northrup, Cynthia Clark (2003), Tariffs and Trade in U.S. History: An Encyclopedia

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smoot%E2%80%93Hawley_Tariff_Act

0 Response to "How Would Fdr Feel About the Hawley-smoot Tariff? How Do You Know This?"

Post a Comment